In Praise of a City

by Ian Findlay

The Hanoi painter Pham Luan has made the city of Hanoi the subject of his art. He walks in the footsteps of a long line of fine artists who have examined the city through all its varied changes. His most recent work on the city and the surrounding countryside show an artist who is gaining in confidence with each new series of oils.

Mimi in Pham Luan’s Studio. 2001

The passion to portray the city in which one lives and works through painting, drawing, and sculpture is one that has been with humankind since the first city was built. A people’s view of their city, whether they actually love art or not, has as much to do with its artists’ works as it has to do with the physical reality developed over time by the authorities. Every city in the world has its devotees and its artists who are obsessed with capturing the nuances and beat of its heart. One merely has to look at the extraordinary range of art that emanated from Paris, London, New York, Seoul, and Tokyo, as well as numerous other cities in the Asia Pacific region during the past century to understand how a city can move artists to explore it in paint. But painting is not merely a way for an artist to make a picture of it, it is also an act of possessing it.

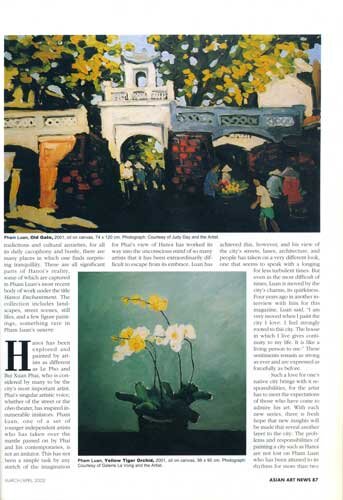

Today, Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam, perhaps more than any other city in Asia, continues to inspire its artists to capture its essence in painting after painting. There is a sense of reverence towards Hanoi from which it is difficult to escape when talking with many Vietnamese artists. It is a city of immense contrasts and vitality, a place with a seemingly all-embracing desire to modernize while, at the same time, retaining something of its very cultured past. It is a city where the tensions of the past and the present are colliding at an alarming rate. Yet, for all the city’s contradictions and cultural anxieties, for all its daily cacophony and bustle, there are many places in which one finds surprising tranquility. These are all significant parts of Hanoi’s reality, some of which are captured in Pham Luan’s most recent body of work under the title Hanoi Enchantment. The collection includes landscapes, street scenes, still lifes, and a few figure paintings, something rare in Pham Luan’s oeuvre.

Hanoi has been explored and painted by artists as different as Le Pho and Bui Xuan Phai, who is considered by many to be the city’s most important artist. Phai’s singular artistic voice, whether of the street or the cheo theater, has inspired innumerable imitators. Pham Luan, one of a set of younger independent artists who has taken over the mantle passed on by Phai and his contemporaries, is not an imitator. This has not been a simple task by any stretch of the imagination for Phai’s view of Hanoi has worked its way into the unconscious mind of so many artists that it has been extraordinarily difficult to escpae from its embrace. Luan has achieved this, however, and his view of the city’s streets, lanes, architecuture, and people has taken on a very different look, one that seems to speak with a longing for less turbulent times. But even in the most difficult of times, Luan is moved by the city’s charms, its quirkiness. Four years ago in another interview with him for this magazine, Luan said, “I am very moved when I paint the city I love. I feel strongly rooted to this city. The house in which I live gives continuity to my life. It is like a living person to me.” These sentiments remain as strong as ever and are expressed as forcefully as before.

Such a love for one’s native city brings with it responsibilities, for the artist has to meet the expectations of those who have come to admire his art. With each new series, there is fresh hope that new insights will be made that reveal another layer to the city. The problems and responsibilities of painting a city such as Hanoi are not lost on Pham Luan who has been attuned to its rhythms for more than two decades. He has seen it through war and an eventful transition to peace, witnessed its opening-up to the world with its inevitable plane loads of tourists whose money and demands of developers have changed the face of the city forever. In the mid-1990s, Luan caught the city and its unique geography in a variety of works that possessed a certain brooding expressionist atmosphere, one in which secrets seemed about to be revealed. In these works there was not the sadness of Phai’s works, but there was occasionally a reverential nod to the master in certain lines to the buildings and a severity to the shadowed streets and alleys.

The changes we see in Luan’s recent series are those of an artist confident in his abilities with color and brush, of someone growing in perception of the world around him, more able to paint beyond the surface. There is freshness to his colors that is so different from the somber tones in many of his earlier pieces. There is a looser, more open component to his style now which is certainly born out of his new-found confidence. And it is part of his strength that he sees this, too. In a recent interview in Hanoi he said, “A big difference is that sometimes I feel that I am more critical and confident in every stroke and in the color contrasts. But sometimes before I felt that I couldn’t make the composition and the emotion work properly for me in a single piece of work. I think that I lacked the experience of working with oils and seeing with oil. That has certainly changed.”

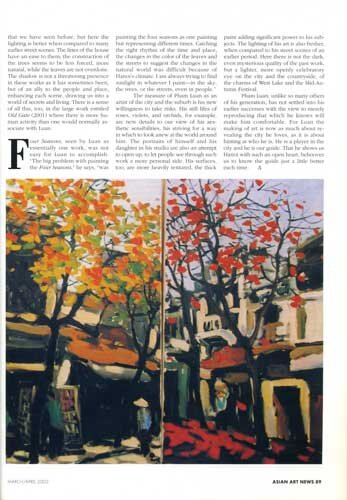

The new rhythm to his work is seen quite clearly in a still life piece such as Yellow Tiger Orchid (2001) and Mimi in Pham Luan’s Studio (2001). These are both simple enough works, uncomplicated in their construction, but they have a sense of spontaneity and freedom of color and line that was not seen in his earlier work. It is also seen in Pink Lotus (2002), Bed of Dahlia (2001), and Fishing Club (2001). Here Luan is clearly not intent on forcing his vision of the world on us; rather, he is inviting us into each scene, drawing us into it through his bold brushstrokes and dabs of subtle color as in Pink Lotus, while in Fishing Club Luan’s device is one in which he utilizes the ripple of water, the stillness of the restaurant where two people (lovers?) speak quietly, and the shadow of the overhanging branches.

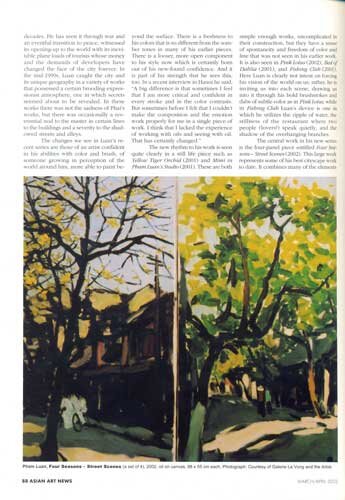

The central work in his new series is the four-panel piece entitled Four Seasons – Street Scenes (2002). This large work represents some of his best cityscape work to date. It combines many of the elements that we have seen before, but here the lighting is better when compared to many earlier street scenes. The lines of the house have an ease to them; the construction of the trees seems to be less forced, more natural, while the leaves are not overdone. The shadow is not a threatening presence in these works as it has sometimes been, but of an ally to the people and place, enhancing each scene, drawing us into a world of secrets and living. There is a sense of all this, too, in the large work entitled Old Gate (2001) where there is more human activity and one would normally associate with Luan.

Four Seasons, seen by Luan as essentially one work, was not easy for Luan to accomplish. “The big problem with painting the Four Seasons,” he says, “was painting the four seasons as one painting but representing different times. Catching the right rhythm of the time and place, the changes in the color of the leaves and the streets to suggest the changes in the natural world was difficult because of Hanoi’s climate. I am always trying to find sunlight in whatever I paint – in the sky, the trees, or the streets, even in people.”

The measure of Pham Luan as an artist of the city and the suburb is his new willingness to take risks. His still lifes of roses, violets, and orchids, for example, are new details to our view of his aesthetic sensibilities, his striving for a way in which to look anew at the world around him. The portraits of himself and his daughter in his studio are also an attempt to open up, to let people see through such work a more personal side. His surfaces, too, are more heavily textured, the thick paint adding significant power to his subjects. The lighting of his art is also fresher, when compared to his street scenes of an earlier period. Here there is not the dark, even mysterious quality of the past work, but a lighter, more openly celebratory eye on the city and the countryside, of the charms of West Lake and the Mid-Autumn Festival.

Pham Luan, unlike so many others of his generation, has not settled into his earlier successes with the view to merely reproducing that which he knows will make him comfortable. For Luan the making of art is now as much about revealing the city he loves, as it is about hinting at who he is. He is a player in the city and he is our guide. That he shows us Hanoi with such and open heart, behooves us to know the guide just a little better each time.